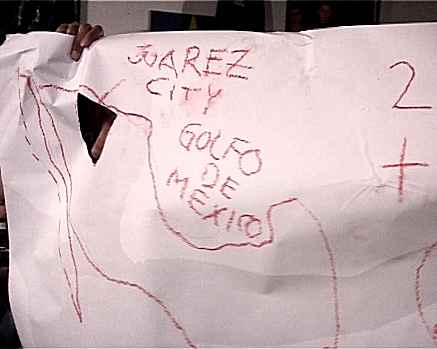

Lorena Mendez

INTERAKCJE 2004

Mexico

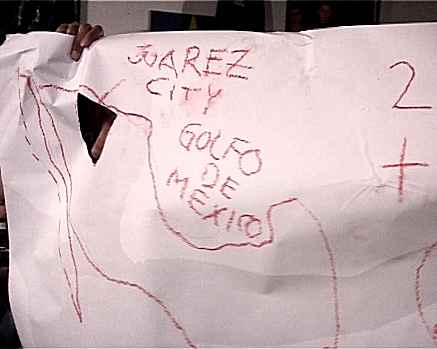

Intolerable Killings:

Ten years of abductions and murders in Ciudad Juárez

and Chihuahua

Summary Report and Appeals

Cases

In Ciudad Juárez, and more recently in the city of Chihuahua, the abduction of Silvia Arce and her mother's appeal for her daughter to be found and for justice to be done are not isolated occurrences. The authorities currently recognize that the fate and whereabouts of around 70 women remains a mystery. For many Mexican non-governmental organizations, the number of women who are missing is more than 400. What is certain is that in the state of Chihuahua, a significant number of cases of young women and adolescents reported missing - in one case an 11 year old - are found dead days or even years later. According to information received by Amnesty International, in the last 10 years approximately 370 women have been murdered of which at least 137 were sexually assaulted prior to death. Furthermore, 75 bodies have still not been identified. Some of them may be those of women who have been reported missing but this has been impossible to confirm because there is insufficient evidence by which to identify them.

[Box]

12 May 1993 - The body of an unidentified woman found ... on the slopes of Cerro Bola (...) in the supine position and wearing denim trousers with the zipper open and the said garment pulled down around the knees (...) penetrating puncture wound to the left breast, abrasions on the left breast, blunt force injury with bruising at the level of the jaw and right cheek, abrasion on the chin, bleeding in the mouth and nose, a linear abrasion near the chin, light brown skin, 1.75 cm., brown hair, large coffee-coloured eyes, 24 years old, white brassière pulled up above the breasts. Cause of death asphyxia resulting from strangulation. (Preliminary Investigation 9883/93-0604, Ciudad Juárez, Chihuahua, February 1998)"

[End Box ]

In a significant number of cases, the brutality with which the assailants abduct and murder the women goes further than the act of killing and provides one of the most terrible examples of violence against women. Many of the women were abducted, held captive for several days and subjected to humiliation, torture and the most horrific sexual violence before dying, mostly as a result of asphyxiation caused by strangulation or from being beaten. Their bodies have been found days or even years later, hidden among rubble or abandoned in deserted areas near the city. "When we found her, my daughter's body told of everything that had been done to her", said Norma Andrade the mother of Lilia Alejandra, whose body was found in February 2001, on waste ground in Ciudad Juárez, next to the maquila(1) where she worked. Like Lilia Alejandra, most of the women, some with children to support, come from poor backgrounds and have to take long bus journeys to reach their places of work or study. Sometimes, they have no choice but to walk alone across unlit waste ground and streets where they are at greater risk of possible attack.

These crimes, classified by the authorities as "serial killings" have shocked the population of Chihuahua, a state which is characterised by high levels of violence against women, including killings as a result of domestic violence or other types of violence.

The first cases of abduction and killing of women and girls exhibiting a similar pattern were reported in Ciudad Juárez ten years ago. Located in the desert on the border with the United States, it is now the most heavily-populated city in Chihuahua state. Its geographical position has turned it into fertile territory for drug trafficking and this has led to high crime levels and feelings of insecurity among the population. However, throughout the past few decades, the establishment of so-called maquilas, assembly plants for export products set up by multinational companies, has also meant that it has been privileged in terms of economic development. The profitability of the maquiladora industry is largely derived from the hiring of very cheap local labour. Despite the low pay, the need for a wage or the desire to get across the border to the neighbouring country to the north in search of a better future has turned Ciudad Juárez into an "attractive" city for a large number of people from different parts of Mexico.

Several of the missing or murdered women were employed in maquilas. Waitresses, students or women working in the informal economy have also been targeted by the assailants. In short, young women with no power in society, whose deaths have no political cost for the local authorities.

In fact, in the first few years after the abductions and murders began, the authorities displayed open discrimination towards the women and their families in their public statements. On more than one occasion the women themselves were blamed for their own abduction or murder because of the way they dressed or because they worked in bars at night. A few years later, in February 1999, the former State Public Prosecutor, Arturo González Rascón, was still maintaining that "Women with a nightlife who go out very late and come into contact with drinkers are at risk. It's hard to go out on the street when it's raining and not get wet".(2)

Over the years, the pressure brought to bear by the families and non-governmental organizations and their calls for the crimes to be clarified have succeeded in attracting national and international attention. Proof of this was the visit and subsequent report on the situation of women in Ciudad Juárez by the Special Rapporteur on the Rights of Women from the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights (IACHR)(3). As a result of the national and international interest in the cases of the women from Ciudad Juárez and Chihuahua, the authorities have been forced to moderate their responses before public opinion on the issue, although they continue to insist on treating each crime in isolation and deny that the abductions and murders of the women and girls in question share common gender-based characteristics.

The failure of the competent authorities to take action to investigate these crimes, whether through indifference, lack of will, negligence or inability, has been blatant over the last ten years. Amnesty International has documented unjustifiable delays in the initial investigations, the period when there is a greater chance of finding the woman alive and identifying those responsible, and a failure to follow up evidence and witness statements which could be crucial. In other cases, the forensic examinations carried out have been inadequate, with contradictory and incorrect information being given to families about the identity of bodies, thereby causing further distress to them and disrupting their grieving process. Other irregularities include the falsification of evidence and even the alleged use of torture by officers from the Chihuahua State Judicial Police, in order to obtain information and confessions of guilt.

The creation in 1998 of the Special Prosecutor's Office for the Investigation of Murders of Women, also failed to live up to the expectation that there would be a radical change in the actions of the state authorities to stamp out such crimes. So far, despite the fact that the institution has had seven different directors, there has been no significant improvement in the coordination and systematizing of investigations in order to put an end to the abductions and murders. The father of María Isabel Nava, for example, reported his daughter missing to the Special Prosecutor's Office on 4 January 2000. However, according to him, instead of taking immediate action, the Special Prosecutor said to him: "It's only Tuesday" and insinuated that his daughter had gone off with her boyfriend. The father replied indignantly: "Are we going to wait until she turns up dead?". His fears were justified. The body of María Isabel Nava was found 23 days later. According to the autopsy, she had apparently been held in captivity for two weeks before being killed.

The situation is made worse by the failure, time and again, to keep the families informed of developments, causing deep distrust of the judicial apparatus and politicians. Furthermore, demands that a formal criminal investigation (averiguación previa, preliminary investigation) be immediately opened from the first day on which a woman is reported missing in order to determine whether a criminal offence such as unlawful detention (privación de libertad) or kidnapping has been committed, have been ignored. According to the authorities, such a request is not appropriate because they claim that the cases of women reported missing are investigated in the same way and with the same degree of urgency as if a formal investigation had been opened. However, in the Mexican justice system, a formal criminal investigation offers better guarantees and forces the State to justify its actions. In the absence of a criminal investigation, the family has no right to justice and is dependent on the good will of the authorities dealing with the case. In Ciudad Juárez and Chihuahua, the ineffectiveness of the investigations have prompted the relatives and friends of the victim themselves, fearing that something bad may have happened to their daughter or sister, to organize searches throughout the city. Responsibility for gathering evidence also falls on them.

However, the relatives do not only have to live with the pain caused by the loss of a loved one and the anguish of not knowing their whereabouts. In Ciudad Juárez and Chihuahua, the authorities have frequently criticized or tried to discredit the work carried out by non-governmental organizations and the relatives in their search for justice. Some organizations have even been publicly accused of using the cases of the women for financial gain without any evidence for such accusations. Worse still have been the threats and intimidation to which lawyers, relatives and members of NGOs have been subjected with no attempt being made to identify those responsible and bring them to justice.

Impunity reigns

As far as the state authorities are concerned, most of the murders - including cases of domestic violence or other types of violence - have been "solved". However, although, according to their figures, 79 people have been convicted, in the vast majority of cases justice has not been done. Impunity is most evident in the case of the so-called "serial murders" that have been recognized as such by the state but in which there has been only one conviction for the kidnapping and murder of a young woman and 18 detainees awaiting the outcome of the judicial process, in some cases for several years. Furthermore, the quality of the investigations and the alleged failure to provide adequate guarantees during the trials cast doubt on the integrity of the criminal proceedings brought against several of those arrested in connection with these crimes. Meanwhile, year after year, the crimes continue. The discovery of the body of Viviana Rayas in May 2003 in the city of Chihuahua and allegations that those arrested in connection with the case were tortured, demonstrate yet again that the abductions and murders in question are far from being solved.

The fact that the state authorities have not managed to clear up or eradicate these crimes has led to much speculation about who might be behind the murders. There is talk of the involvement of drugs traffickers, organized crime, of people living in the United States, as well as rumours that those responsible are being protected. There are also theories about the motives being connected with satanism, the illegal trade in pornographic films and the alleged trafficking of organs. However, at the moment, since the investigations have so far not been able to confirm any of them, such hypotheses are simply helping to fuel even greater fear among Chihuahuan society.

For years the federal authorities overtly kept out of the investigations on the grounds that, unlike, for example, organized crime, the murders of women in Chihuahua state did not come under their jurisdiction as they were not federal crimes. However, during 2003, the Office of the Attorney-General, has confirmed that it has claimed jurisdiction over several cases on the grounds that they may constitute federal offences and this could give a significant boost to the investigations. Given the scale of these crimes, Amnesty International believes that, in order to prevent, punish and stop the abduction and murder of women in Ciudad Juárez and Chihuahua as well as the abuses of power which have hindered the earlier investigations, it is essential for mechanisms to be set up to ensure proper coordination between all authorities at municipal, state and federal level.

The Ciudad Juárez and Chihuahua cases display many of the features which undermine the credibility of the Mexican justice system and foster impunity. Amnesty International has repeatedly called for a profound structural reform of the justice system to be undertaken in order for its investigative procedures and capabilities to be able to provide full access to justice for the victims and a fair trial for the accused by ensuring that all their rights are guaranteed.

The inability of the state authorities to address these violent offences against women also means that Mexico is in breach of international conventions to which it is a party, including standards that are specifically aimed at eliminating violence against women.

The violence against women demonstrated in these cases is not only a form of discrimination but also constitutes violations of the rights to life, physical integrity, liberty, security and legal protection enshrined in the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights, the American Convention of Human Rights and the Convention of the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination against Women (CEDAW)(4), among others. These international standards reaffirm the State's obligation to establish the truth, dispense justice and provide reparations to victims, even when their rights have been violated by private individuals.

The Americas is the only continent which has a binding treaty specifically

directed at combatting violence against women: the Inter-American Convention for

the Prevention, Punishment and Eradication of Violence against Women (Convention

of Belem do Pará).(5) The Inter-American system also set a precedent when,

fifteen years ago, it reaffirmed that the State incurs a responsibility at the

international level when it fails to exercise due diligence in investigating and

punishing human rights abuses committed by private individuals, thereby

establishing a doctrine which is particularly relevant for women who are

suffering systematic violence in the domestic domain and in the

community.

The full document, entitled "Mexico: Intolerable killings -

Ten years of abductions and murders in Ciudad Juárez and Chihuahua" (AI Index:

AMR 41/026/2003), addresses the inability of the Mexican authorities to treat

the cases in the context of a specific pattern and their failure to provide the

relatives with a proper response or effective legal remedy. Through the use of

specific cases, the report provides an analysis of the state's failure to

exercise due diligence in preventing, investigating and punishing the crimes in

question. It also sets out Mexico's obligations under international human rights

standards and includes a series of conclusions and a set of recommendations

which, in Amnesty International's opinion, need to be fully and effectively

implemented. The appeal cases described below provide an example of ten years of

intolerable crimes.

[Box]

Amnesty International's recommendations

- The federal, state and municipal authorities must publicly recognize and condemn the abductions and murders of women in Ciudad Juárez and Chihuahua and stress the dignity of the victims and the legitimacy of the relatives' efforts to obtain truth, justice and reparations.

- The state and federal authorities must ensure that prompt, thorough, effective, coordinated and impartial investigations into all cases of abduction and murder of women in Chihuahua state are carried out and given the necessary resources.

- The federal government must urgently address society's demand regarding who has jurisdiction to investigate the abductions and deaths of women in Chihuahua state so that effective, quick and thorough investigations backed up with resources, experts and the full cooperation of all other authorities can take place.

- The State must establish an urgent search mechanism so that, in the event that a woman is reported missing, a criminal investigation can be opened under the supervision of a judge with full powers to determine the whereabouts of the missing person and to follow up any relevant leads in order to determine whether an offence has been committed.

- Any negligence, failure to act, complicity or tolerance on the part of state officials in connection with the abductions and murders of women in Chihuahua state must be investigated and punished. Any state official suspected of committing serious human rights abuses such as torture or covering up abductions must be removed from his or her post pending the outcome of an impartial investigation.

- The federal, state and municipal must allocate sufficient resources to improving public safety in the state and preventing violence against women in the community, including by installing lighting and setting up security patrols.

- The Mexican State must ensure that the maquilas meet their legal obligations to their employees, with special emphasis on the physical, sexual and mental wellbeing of the female workers.

- The authorities must ensure that, in line with the UN Declaration on Human Rights Defenders, defenders of women's rights and relatives' associations who are working to put an end to violence against women can carry out their legitimate work without fear of reprisals and with the full cooperation of the authorities.

- The authorities must implement the international recommendations addressed to Mexico since 1998 by the Special Rapporteurs of the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights and the United Nations, as well as by the UN Committee on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination against Women, all of whom have studied the cases of the women from Ciudad Juárez and Chihuahua.

- The authorities must implement the international recommendations addressed

to Mexico since 1998 by the Special Rapporteurs of the Inter-American Commission

on Human Rights and the United Nations, as well as by the UN Committee on the

Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination against Women, all of whom have

studied the cases of the women from Ciudad Juárez and Chihuahua.

[End

Box]

At 10.15pm on 19 February 2001, people living near waste ground close to a maquila in Ciudad Juárez dialed 060, the municipal police emergency number, to inform them that an apparently naked young woman was being beaten and raped by two men in a car. No patrol car was dispatched in response to the first call. Following a second call, a police unit was sent out but did not arrive until 11.25pm, too late to intervene. The car had already left.

Four days earlier, the mother of Lilia Alejandra García Andrade had reported her 17-year-old daughter missing to the Unidad de Atención a Víctimas de Delitos Sexuales y Contra la Familia, Unit for the Care of Victims of Sexual Offences and Offences against the Family. Lilia Alejandra, the mother of a baby and a three-year-old boy, worked in a maquiladora called Servicios Plásticos y Ensambles. At 7.30pm on the previous night, her colleagues had seen her walking towards an unlit area of waste ground next to the factory. Lilia Alejandra used to cross it every day to catch the bus home. But that night she never reached her destination.

On 21 February the body of a young woman was found on the waste ground near to where the emergency call had been made. It was wrapped in a blanket and showed signs of physical and sexual assault. The cause of death was found to be asphyxia resulting from strangulation. The body of the young woman was identified by the parents as being that of Lilia Alejandra. The forensic report concluded that she had died a day and a half earlier and that she had spent at least five days in captivity prior to her death. A report from the police switchboard taken at 11.05pm on 19 February simply states "nothing to report" ("reporte sin novedad"). The identity of the woman attacked that day was never established and no attempt was made to investigate whether there was any connection between that incident and the abduction of Lilia Alejandra or any other case. The authorities never investigated the lack of response on the part of the 060 Emergency Switchboard in Ciudad Juárez. There is still no lighting on the waste ground next to the maquiladora. A small cross commemorates the place where the body was found.

Despite the fact that crimes of this kind had been happening in Ciudad Juárez

for eight years, the authorities had been unable to establish effective

emergency response systems, which is particularly worrying in cases where an

apparent abduction and rape have been reported. Worse still, the state

authorities failed to review the mistakes made in this case and denied that

there was any connection between the emergency call and the abduction and murder

of Lilia. No disciplinary action has been reported.

[Box]

WHAT CAN YOU DO?

If you wish to

campaign on behalf of Lilia Alejandra García:

►Write to the Mexican authorities and the Mexican Embassy in your country highlighting the following points:

→ expressing your deep concern at the fact that the state authorities did not

respond effectively to the report that Lilia Alejandra was missing, denied any

connection between the emergency call and the abduction and murder of Lilia

Alejandra, did not launch disciplinary measures or take into account the

mistakes made, and did not carry out a thorough and effective investigation so

that those responsible could be brought to justice;

→ requesting the

authorities to carry out an immediate review of its emergency response systems

and to introduce effective measures for locating people who are reported

missing, including installing telephones in marginalised communities which work

24 hours a day. Effective procedures must be established to locate women who

have been abducted, such as, the carrying out of immediate searches with the

help of relatives. Such searches must continue until the victim is found. The

search must be supervised by a judge who must be able to count on the immediate

collaboration of other judges, prosecutors and the police;

→ requesting

the authorities to investigate the alleged negligence, tolerance, failure to act

and complicity on the part of state officials in investigating the abduction and

murder of the women in question. Such acts must be viewed as serious abuses of

authority and those responsible must be brought to justice. Any official under

investigation must be immediately suspended;

→ requesting the state to

acknowledge its responsibility for the negligence shown in the investigation of

the abduction and murder of Lilia Alejandra and its duty to provide reparations

to the family, as well as to recognize the legitimate work being done by

non-governmental organizations in their struggle for justice.

► Publicize

this case in the local and national media of your country.

► Distribute

details of this case to individuals or groups whom you think may be interested.

[End Box]

Appeals to:

President of

Mexico:

Lic. Vicente Fox Quesada, Presidente de los Estados Unidos de

México , Residencia Oficial de «Los Pinos», Col. San Miguel

Chapultepec, México D.F., C.P. 11850, México. Fax:+ 52 5 2 77 23 76 Salutation:

Dear President

Governor of Chihuahua State: Lic. Patricio Martínez,

Gobernador del Estado de Chihuahua Aldama 901,

Colonia Centro, Estado

de Chihuahua, México. Fax:+ 52 614 429 3464, Salutation: Dear

Governor

Chihuahua State Public Prosecutor: Lic. Jesús José Solís,

Procurador General de Justicia del Estado de Chihuahua. Calle Vicente Guerrero

616, Col. Centro, Estado de Chihuahua, México. Fax:+ 52 614 415 0314

Salutation: Dear Sir

Copy to: Mexican Commission for the Defence and

Promotion of Human Rights:

Comisión Mexicana de Defensa y Promoción de

los Derechos Humanos A.C. (CMDPDH)

Tehuantepec 155, Col. Roma Sur, México DF,

CP 5584 2731, México. E-mail: cmdpdh@laneta.apc.org

Bring Our Daughters

Home: Nuestras Hijas de Regreso a Casam Calle 5 de Mayo, No. 859, Norte o

No. 321, a 2 calles del Malecón, Colonia Hidalgo/Partido Romero, Ciudad Juárez,

Estado de Chihuahua, México

WHAT CAN YOU DO?

If you would like to campaign on behalf of Silvia Arce and Griselda Mares:

► Write to the Mexican authorities and the Mexican Embassy in your country highlighting the following points:

→ expressing concern at the failure to provide an adequate response in the cases of Silvia Arce and Griselda Mares or take effective measures to locate them or improve mechanisms to identify those responsible as soon as possible;

→ expressing deep concern at the delays and the inability of the police to officially record all the information in the case file, follow up possible leads or take comprehensive statements from possible witnesses in order to clarify the circumstances surrounding the abduction of Silvia and Griselda;

→ expressing deep concern that the PGR has not investigated the possible involvement of the federal police office in the abduction of Silvia and Griselda;

→ urging the authorities to carry out an immediate and thorough investigation into the possible involvement of police officers from the PGR in the cases of Silvia and Griselda;

→ requesting the state to acknowledge its responsibility for the negligence demonstrated in the investigation of the cases of Silvia and Griselda and the pain caused to their families; to recognize their legal right to assist in the investigations; to receive appropriate reparations; and the legitimate work of the non-governmental organizations in their struggle for justice;

► Publicize this case in the local and national media in your country.

► Distribute details of the case to individuals or groups whom you think

might be interested.

[End Box]

Appeals to:

President of Mexico:

Lic. Vicente Fox Quesada, Presidente

de los Estados Unidos de México

Residencia Oficial de «Los

Pinos»

Col. San Miguel Chapultepec

México D.F., C.P. 11850, México

Fax:

+ 52 5 2 77 23 76

Salutation: Dear President

Attorney General of the

Republic

General Rafael Marcial Macedo de la Concha

Procurador

General de la República

Procuraduría General de la República

Reforma

Norte esq.Violeta 75, Col. Guerrero

Delegación Cuauhtémoc, México D.F., C.P.

06300

Fax: (+525 55) 346 0983/ 0908 (pedir tono de fax)

Salutation:

Dear Attorney General

Governor of Chihuahua State:

Lic. Patricio

Martínez,

Gobernador del Estado de Chihuahua

Aldama 901, Colonia

Centro

Estado de Chihuahua, México

Fax: + 52 614 429 3464

Salutation:

Dear Governor

Chihuahua State Public Prosecutor:

Lic. Jesús José

Solís,

Procurador General de Justicia del Estado de Chihuahua

Calle

Vicente Guerrero 616

Col. Centro, Estado de Chihuahua, México

Fax: + 52

614 415 0314

Salutation: Dear Sir

Copy to:

Mexican Commission

for the Defence and Promotion of Human Rights: Comisión Mexicana de Defensa

y Promoción de los Derechos Humanos A.C. (CMDPDH),

Tehuantepec 155, Col.

Roma Sur,

México DF, CP 5584 2731

E-mail:

cmdpdh@laneta.apc.org

Justice for Our Daughters:

Justicia para

Nuestras Hijas

Río Soto La Marina 8204,

Col. Alfredo Chávez,

Chihuahua, Estado de Chihuahua, México

Chihuahua Independent Human

Rights Committee:

Comité Independiente de Chihuahua Pro-Defensa de

Derechos Humanos (CICH)

Ecuador No. 526 Sur, Col. El Barreal, Ciudad Juárez,

Chihuahua, México

► Write to the Mexican authorities and the Mexican Embassy in your country highlighting the following points:

→ expressing deep concern at the contradictory and incorrect information provided by the forensic authorities to the families of the eight women whose remains were found in November 2001 and at the terrible emotional impact that this has had on the families;

→ stressing the need for the forensic services at both the state and federal level to be independent from the prosecuting authorities, for them to be given sufficient resources to carry out their work and for mechanisms to be set up to ensure that their work can be independently evaluated;

→ requesting that the forensic team receive specialist training to ensure compliance with international standards on forensic methodology and human rights, including the perspective of gender and human rights;

→ requesting the Public Ministry to ensure that the identity of victims is determined objectively and quickly. In the event that results are contradictory, examinations must be carried out again, with the consent of the families, by properly qualified external experts. Once the identity of the victim has been determined with certainty, the body or remains must be handed over to the families without delay;

→ urging the authorities to carry out an objective investigation into the allegations that the two men arrested in connection with the crimes in question were tortured, bring those responsible to justice and ensure that any evidence extracted as a result of torture or ill-treatment is not admitted into the trial proceedings;

→ requesting the authorities to guarantee the safety of the relatives and the lawyer of VÝctor Javier GarcÝa and Gustavo Gonzßlez Meza, in view of the persistent threats they have received, and that those responsible be brought to justice;

→ calling on the authorities to carry out a thorough and effective investigation into the death of Gustavo Gonzßlez Meza.

► Publicize this case in the local and national media in your country.

► Distribute details of this case to individuals or groups you think may be

interested.

[End box]

Appeals

to:

President of Mexico: Lic. Vicente Fox Quesada, Presidente

de los Estados Unidos de México , Residencia Oficial de «Los Pinos».Col.

San Miguel Chapultepec,México D.F., C.P. 11850, México, Fax:+ 52 5 2 77 23 76,

Salutation: Dear President

Governor of Chihuahua State: Lic. Patricio

Martínez, Gobernador del Estado de Chihuahua, Aldama 901, Colonia

Centro,

Estado de Chihuahua, México, Fax: + 52 614 429 3464, Salutation: Dear

Governor

Chihuahua State Public Prosecutor: Lic. Jesús José Solís,

Procurador General de Justicia del Estado de Chihuahua,

Calle Vicente

Guerrero 616, Col. Centro, Estado de Chihuahua, México,Fax: + 52 614 415 0314,

Salutation: Dear Sir

Copy to: Mexican Commission for the Defence and

Promotion of Human Rights:

Comisión Mexicana de Defensa y Promoción de

los Derechos Humanos A.C. (CMDPDH), Tehuantepec 155, Col. Roma Sur

México DF,

CP 5584 2731, México, E-mail:cmdpdh@laneta.apc.org

Bring Our Daughters

Home: Nuestras Hijas de Regreso a Casa, Calle 5 de Mayo, No. 859, Norte o

No. 321, a 2 calles del Malecón, Colonia Hidalgo/Partido Romero, Ciudad Juárez,

Estado de Chihuahua, México

Women's organization in Ciudad Juárez:

Integración de Mujeres por Juárez

Bulevar Zaragoza 6939, Fraccionamiento

Oasis Oriente, Ciudad Juárez, Estado de Chihuhua,

México

Falsifying evidence: the case of Paloma Angélica Escobar

Ledesma

On 3 March 2002 the mother of 16-year-old Paloma Angélica

Escobar Ledesma, a worker at the Aerotec maquila in the city of

Chihuahua, reported her daughter missing to the Preliminary Investigations

Department, in Chihuahua. That same day, Commander Gloria Cobos Ximello, Head of

the Sexual Offences Unit of the State Public Prosecutor's Office (PGJE) in

Chihuahua was put in charge of the investigation.

Paloma had left her

home at 3.15pm on 2 March and was seen that day at 3.30pm at the Ecco School.

Her family's search to find her alive was in vain. On 29 March Paloma's body was

found in bushes at Km 4 along the road that goes from Chihuahua to Aldama.

According to the autopsy, she was wearing several undergarments, one of which,

according to her relatives, did not belong to her. She had been dead for over 20

days and the only remaining evidence of the identity of her killer was the pubic

hair found on her hands. On 30 March officers of the Judicial Police said they

had found a photograph of the suspected assailant at the site where the body had

been found. That same day, on the basis of that evidence, Paloma's ex-boyfriend

was arrested. Next day, two witnesses gave statements to representatives of the

PGJE claiming that the same photograph had been handed over to Commander Gloria

Cobos the day before, at her request, by a former girlfriend of the man in

custody who did not know that it was going to be used for that purpose.

According to a witness, the photograph, which had been in good condition when

handed over, was found, one day later, to be dirty and creased.

As a

result, that same day, 31 March, the PGJE gave orders for the man to be released

and for an internal inquiry into the actions of the Commander in "planting"

evidence. In April 2002, the Office of the Chihuahua State Public Prosecutor,

suspended the Commander and opened an investigation on grounds of abuse of

authority and making false accusations. The charge originally recorded in the

case file was abuse of authority but an administrative judge is currently only

pursuing the lesser charge of making false accusations. Following a year of

persistent requests from the family, in January 2003 Commander Cobos appeared

before the Preliminary Investigations Department. However, she refused to answer

any questions relating to her conduct of the case.

With regard to the

investigations, despite the fact that a week after Paloma went missing the

Sexual Offences Unit had obtained a statement from a key witness regarding the

identity of the possible culprits, it was only at the end of May 2002 that

several official letters were issued calling for the suspects to be found. From

the case dossier it appears that investigation of the individuals against whom,

according to witnesses, evidence was strongest came to a halt. The men concerned

left the city and the authorities claim that they lost trace of them. So far

they have not been located in order to make new

statements.

[Box]

WHAT CAN YOU DO?

If you

wish to campaign on behalf of Paloma Escobar Ledesma:

► Write to the Mexican authorities and the Mexican Embassy in your country highlighting the following points:

→ expressing deep concern at the way in which the evidence was falsified and the inability of the authorities to investigate the case and ensure that those responsible for the abduction and murder of Paloma Escobar Ledesma were brought to justice;

→ expressing deep concern at the delays and the inability to follow up possible leads and take comprehensive statements from possible witnesses in order to clarify the circumstances surrounding the death of Paloma;

→ requesting the authorities to investigate the alleged negligence,

tolerance, failure to act and complicity on the part of state officials with

regard to the abduction and murder of women. Such acts must be viewed as serious

abuses of authority and those found to be responsible must be brought to

justice. Any official under investigation must be immediately

suspended;

→ requesting the state to acknowledge its responsibility for

the lack of due diligence demonstrated in the investigation of the abduction and

murder of Paloma Escobar Ledesma and the pain caused to her family, guarantee

their safety and the right to assist in the investigations and ensure that they

receive the reparations they are due to be awarded;

► Publicize this case in the local and national media in your

country.

► Distribute details of this case to individuals or groups you

think may be interested.

[End Box]

Appeals to:

President of Mexico:

Lic. Vicente Fox Quesada, Presidente

de los Estados Unidos de México

Residencia Oficial de «Los

Pinos»

Col. San Miguel Chapultepec

México D.F., C.P. 11850, México

Fax:

+ 52 5 2 77 23 76

Salutation: Dear President

Governor of Chihuahua

State:

Lic. Patricio Martínez,

Gobernador del Estado de Chihuahua

Aldama 901, Colonia Centro

Estado de Chihuahua, México

Fax: + 52 614

429 3464

Salutation: Dear Governor

Chihuahua State Public

Prosecutor:

Lic. Jesús José Solís,

Procurador General de Justicia

del Estado de Chihuahua

Calle Vicente Guerrero 616

Col. Centro, Estado de

Chihuahua, México

Fax: + 52 614 415 0314

Salutation: Dear

Sir

Copy to:

Mexican Commission for the Defence and

Promotion of Human Rights:

Comisión Mexicana de Defensa y Promoción de

los Derechos Humanos A.C. (CMDPDH),

Tehuantepec 155, Col. Roma Sur

México

DF, CP 5584 2731, México

E-mail: cmdpdh@laneta.apc.org

Justice for

Our Daughters:

Justicia para Nuestras Hijas

Río Soto La Marina 8204,

Col. Alfredo Chávez,

Chihuahua, Estado de Chihuahua, México

E-mail:

gomezg@prodigy.net.mx

Criminal investigations refused: the cases of Rosalba, Julieta, Yesenia and Minerva

Photocaption: Photographs of Yesenia, Minerva, Rosalba and Julieta published in the electronic bulletin published by the Office of the Chihuahua State Public Prosecutor.

In January 2003, the mother of Rosalba, together with the mothers of

Julieta Marleng and Minerva, filed a complaint for kidnapping with the Office of

the Chihuahua State Public Prosecutor (PGJE). On 23 January the PGJE decided to

reject the request and returned the case dossier to the unit which had been

dealing with it up until then. That decision apparently shut off all legal

channels through which the case could be brought before a serious crimes

investigation unit, as should happen with the type of offences that the

testimonies would seem to indicate. The lack of supervision by an independent

judicial body of the initial investigation conducted by the PGJE seriously

limits the ability of the family to effectively appeal the decisions of the

PGJE.

[Box]

WHAT CAN YOU DO?

If you wish to campaign on behalf of Rosalba Pizarro Ortega, Julieta Marleng González Valenzuela, Yesenia Concepción Vega Márquez and Minerva Torres Abeldaño:

► Write to the Mexican authorities and the Mexican Embassy in your country highlighting the following points:

→ expressing deep concern at the lack of effective response to the cases of the four young women and at the fact that the state has not taken effective measures to locate the missing women or improved the mechanisms set up to identify those responsible as soon as possible;

→ expressing deep concern at the delays and the inability to follow up possible leads or take comprehensive statements from possible witnesses in order to clarify the circumstances surrounding the cases of the four young women;

→ requesting the authorities to investigate the alleged negligence,

tolerance, failure to act and complicity on the part of state officials in the

abduction and murder of women. Such acts must be viewed as serious abuses of

authority and those found responsible must be brought to justice. Any officer

under investigation must be immediately suspended;

→ requesting the state

to acknowledge its responsibility for the negligence demonstrated in the

investigations of the cases of Rosalba Pizarro Ortega, Julieta Marleng Gonzßlez

Valenzuela, Yesenia Concepci¾n Vega Mßrquez and Minerva Torres Abelda±o,

adequate reparations for the families and recognizes the legitimate work of

non-governmental organizations in their struggle for justice;

► Publicize

this case in the local and national media in your country.

► Distribute

details of this case to individuals or groups whom you think may be

interested.

[End Box]

Appeals

to:

President of Mexico:

Lic. Vicente Fox Quesada,

Presidente de los Estados Unidos de México

Residencia Oficial de «Los

Pinos»

Col. San Miguel Chapultepec

México D.F., C.P. 11850, México

Fax:

+ 52 5 2 77 23 76

Salutation: Dear President

Governor of Chihuahua

State:

Lic. Patricio Martínez,

Gobernador del Estado de Chihuahua

Aldama 901, Colonia Centro

Estado de Chihuahua, México

Fax: + 52 614

429 3464

Salutation: Dear Governor

Chihuahua State Public

Prosecutor:

Lic. Jesús José Solís,

Procurador General de Justicia

del Estado de Chihuahua

Calle Vicente Guerrero 616

Col. Centro, Estado de

Chihuahua, México

Fax: + 52 614 415 0314

Salutation: Dear

Sir

Copy to:

Mexican Commission for the Defence and

Promotion of Human Rights:

Comisión Mexicana de Defensa y Promoción de

los Derechos Humanos A.C. (CMDPDH),

Tehuantepec 155, Col. Roma Sur

México

DF, CP 5584 2731, México

E-mail: cmdpdh@laneta.apc.org

Justice for

Our Daughters:

Justicia para Nuestras Hijas

Río Soto La Marina 8204,

Col. Alfredo Chávez,

Chihuahua, Estado de Chihuahua, México

E-mail:

gomezg@prodigy.net.mx

********

(1) Maquilas or maquiladoras are factories set up by US and other foreign companies to exploit cheap labour and favourable tariffs in the region near the US border.

(2) El Diario de Juárez, 24 February 1999.

(3) "The Situation of the Rights of Women in Ciudad Juárez, Mexico: The Right to be Free from Violence and Discrimination", March 2003. Report by the IACHR Special Rapporteur on the Rights of Women, Marta Altolaguirre.

(4) The Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination against Women (CEDAW) was ratified by Mexico on 23 March 1981.

(5) The Inter-American Convention for the Prevention, Punishment and Eradication of Violence against Women (Convention of Belem do Pará), adopted in Belem Do Pará, Brazil, on 9 June 1994 and ratified by Mexico on 12 November 1998.

| AI INDEX: AMR 41/027/2003 11 August 2003 |

|

Related Documents | ||||||

|